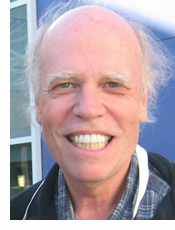

If you’re attending a conference on forward thinking ways to help kids learn, or maybe an event on learning through video games, chances are you will be listening to thoughts offered by James Paul Gee. Dr. Gee is a noted expert on the topic of video games and learning. He is the Mary Lou Fulton Presidential Professor of Literacy Studies at Arizona State University and is a member of the National Academy of Education. His work has been published widely in journals in linguistics, psychology, the social sciences and education. Dr. Gee’s recent book, What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy argues that good video games are designed to enhance learning through effective learning principles supported by research in the Learning Sciences. His new book, Women and Gaming: The Sims and 21st Century Learning, written with Elisabeth R Hayes, will be available this coming May, 2010. At the recent Breakthrough Learning in a Digital Age conference held at the Google headquarters, I had the opportunity to speak with James. You can view a short video of my interview with Dr. Gee on the Cooney Center YouTube channel or read the complete interview below. Portions of this interview were edited for clarity:

What successes do you see in the learning games movement?

Why do you think games are not perceived as effective learning tools?

Would a funding approach that is similar to public television be a good model for the learning games industry?

What excites you when you see kids developing their own games?

How are learning games best used to accelerate learning?

INTERVIEW:

Scott Traylor: Where do you think things stand today with the learning games movement? What successes do you see?

James Paul Gee: Successes have been slow in coming, much more slowly than I would have thought, but they are coming. What I’m seeing is the beginning of noncommercial games for learning.

Looking back on the gaming industry, developers made products that were expectable, products that were designed by baby boomers and made by principles of instructional technology. These games didn’t break the mold, and didn’t break out of a pattern. They were not good games and did not include good learning. Today we’re beginning to see games being developed by young game designers who understand learning and understand game design. They’re making good games, and they are making things that work. Over the next few years we’re going to see a real explosion in better products. Some of this has to do with the appearance of the independent game studios. In the commercial world the independent games community has been very slow to develop. For a while there really was none, but now with downloading services across all major platforms, you’re seeing many independent games being developed. Games like Flower and Braid, made with relatively small budgets, but they are really top games. Independent games like these are doing as well as many of the commercial games out on the market, and they’re setting the standard for so called “serious games, ” games that have the ability to teach. If we can make commercial games that are as good as Flower or Braid for a modest budget, we certainly can make games in the learning sphere that are equally as good. (Return to Question Picker)

Traylor: Why do you think games are not perceived as effective learning tools?

Gee: I think the major reasons are cultural, along with the slow development of an independent game industry, but also the power of baby boomers. People of my age, baby boomers, have theories and are in relatively solid positions in institutions. They get to call the shots, but this is a changed world. We’re talking about learning and using technologies that people under thirty know a lot more about. It’s not surprising when they apply our theories and do a better job than when we applied our theories. I think that’s all good, we need to release that creative energy.

The other thing you touch on, and it’s a very serious matter, is that we really don’t have many new business models. Think about it. We’re trying to make things that do social good, but if the social good is done for free, it dies when the grant ends. Right? We now realize we have to think about how to make products that can go on for a long period of time, and at some level earn enough money to sustain themselves while still doing social good. Lots of people are now thinking about how we can create new and innovative business models so that everybody wins. Models that allow people to make enough money and at the same time spur new businesses, new enterprises to open up, models which will help everybody benefit. Until we really get that down, what you’ll end up seeing are products that are made on government dollars that die the day the grant is over. The same is true with academic research, the day the grant money stops coming in the research stops. (Return to Question Picker)

Traylor: Would you suggest a financial approach that is similar to public television? Would that be a good model for growing a learning games industry?

Gee: There’s going be a whole new set of models. Open source, the public sharing of programming resources, is one very important area. A public television model around games that would include both design workshops as well as giving out products, and also encouraging consumers to make products, would certainly be one model. We just have to have new models for new businesses. There are going to be “double bottom line” businesses; businesses that are committed to social good by solving our educational problems but these same businesses would be committed to making money. Making money not just to enrich individuals, but to also keep the social good going. There are a number of models we can think of for that. As is true of many academics, we didn’t think that business models were important. Now people are starting to see that business models are needed to bring about long-term impact. (Return to Question Picker)

Traylor: What excites you when you see kids developing their own games?

Gee: I’m excited that so many young people today are taking gaming beyond gaming. They’re not just playing games. They’re making games. They’re designing things for games. They’re setting up discussions and guilds and websites around games. They’re learning new software, software that contributes to these sites and discussions and products. And very often, they organize themselves into learning communities to do all of this. Their passion for learning in these communities grows beyond their passion for the games themselves. In other words, it’s a trajectory towards learning communities, and towards thinking like a designer, and producing, and not just consuming, that some of our best games give rise to.

The video game Spore is a great example. Spore is designed so that you play, and then you design, and then you play, and you join a community, and you get the products you have designed to appear within the game, and then you design with others collaboratively. This game provides very good tools to do that. Anyone, from the very young to the very old, can play.

Another great example is the game Little Big Planet. There’s a whole bunch of products coming out that say why don’t you see playing and designing as things you can do together in a game. These things are integrated together, so the game becomes as much your product as it is ours, and becomes a community event and not just an individual event. The lessons here for education are massive, because it means we’re going have to start designing, not just pieces of software, but ways for people to set up learning communities that they’re productive within. (Return to Question Picker)

Traylor: So the perception that learning games alone will result in really good learning outcomes, is not the full story. What you’re saying is that learning games, supported by learning communities, are really the combination that accelerates the learning opportunity?

Gee: Those of us who study learning games make the distinction between a game, which is just the software, and the game with a capital “G”, which is the whole set of social learning interactions built around the game. We used to argue, if you’re going to use games for learning, you have to have a community of learning built around the game. Now the commercial industry realizes you won’t make money if you don’t build a learning community around the game. It’s an integral part to gaming, to participate in a collaborative community around the game.

My work has never been that of an advocate to put games into schools. That’s a fine thing to do, but that’s not what my work is about. It’s about putting the learning found in games into schools, learning that’s centered on problem solving and collaboration.

In school students get a bunch of facts and information. You can’t solve problems with it, so you get nothing. The interesting thing is if I make you solve a problem, and I really design the experience of that problem, guiding you and mentoring you, which is what good game design does, you get problem solving and you get facts and information, because you have to learn that in order to solve the problem. I will also get you to collaborate in a community where you might even innovate. You’re going to design new things and do new stuff. I want to see that model go into schools and that model doesn’t have to be a game. We can do that in the world in many different ways.

The other thing I really want to stress about games is that, in my opinion, it’s not a good idea to try to teach a whole curriculum through games. Industries are building up to try to do this. It’s too expensive. We want to learn in many different ways. Games are particularly good for preparation for future learning. If you want to motivate somebody in an area like chemistry or physics, a game is an ideal way to not only motivate that learning, to get learners to see why you do it, what is good about it, why it would be a turn on to do it, but it also prepares them to get ready for learning in the future. That future learning doesn’t have to occur in games. We tend to get obsessed with one platform, but just like in the world where kids don’t just game, they also go on the internet, and they write fiction, and they mod games. They do a whole bunch of stuff. We want our curriculum to be a whole bunch of stuff as well. (Return to Question Picker)

Average Rating: 5 out of 5 based on 170 user reviews.