January 10th, 2012

[The following is an article I wrote for the January 2012 issue of Children’s Technology Review. A PDF reprint of the article can also be found here]

If somebody asked you to name the masters of interactive design, chances are good that Will Wright would be on your list. He created SimCity which led to SimAnt, The Sims, and Spore, and he’s currently working on a new social game called HiveMind. Last year in New York, I heard him speak and was struck by his thoughts about the learning opportunities he brings to his players, and asked him about it. What does he think about when he makes a game? What are some key influences? (Note that this was a long interview, and edits have been made for clarity).

Scott Traylor: In your presentations you often refer to learning theory, including your own Montessori education. It seems you have a passion for the topic.

Will Wright: Learning theory is certainly one of the factors that shapes my talks and my work in general, but it’s only one element. For me, making a game or a talk is a process of continual self-discovery.

Scott: Can this be attributed to your Montessori background?

Will: Montessori is good for self-discovery and exploration, but Montessori didn’t invent it. Self-discovery and exploration have existed for millennia before Montessori. it’s the way the human brain works. The whole constructivist approach to education simply leverages hardware that’s already built in.

Scott: When you say “constructivist” is it fair to say that you are thinking of Piaget and perhaps Seymore Papert?

Will: Oh, yes, and Alan Kay as well. This formalized approach to learning has really only been around for maybe a 100 years. We can go back hundreds and hundreds of years before that and see people understood this as the primary mode of learning. Consider the Renaissance and Leonardo Da Vinci. At some point the pedagogy got wrapped around that inherent process. It’s something that has remained, almost becoming more relevant in terms of its implications with modern technology, or our imaginations, and our creativity. It’s almost more relevant now where people can approach a wider range of endeavors creatively, because of the tools we have, for gathering information, for creating things, for sharing things.

Scott: So you’re saying we’re at a point, technically speaking, where we are empowered as creators, as explorers, in anything that might interest us?

Will: Yes, especially in things like the social dimension. I can create something and put it up on the web and then by tomorrow 1, 000 people might’ve seen it. Think back 100 years ago what it would have taken for that to happen. It just wasn’t a possibility then, but now it’s a possibility for anyone.

Scott: While these theories have become more formalized in the last century or so, good teachers and good facilitators of learning have been aware of these things for ages. Now there’s the opportunity for learning to be amped up through technology and through participation in a way we have never experience before, in such an immediate way.

Will: Yeah, Seymour Papert and Alan Kay were among the first people to realize the impact that modern technology was going to have. Nicholas Negroponte, as well.

Scott: When you talk about games, or video games, you often refer to these things as playful objects. Is that intentional?

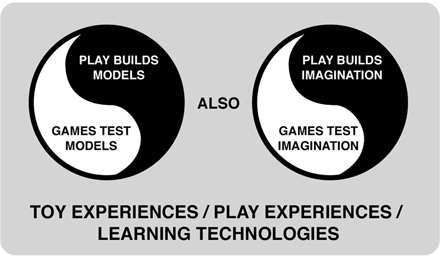

Will: Let’s take a look at that. People like to call the things I make games, but I tend to think of them as toys. There really needs to be more open-ended play experiences and that’s a broader world than the formal definition of games. I think a game is really a subset of the world of play. In substance it’s really just semantics but it’s cultural as well. A lot of people think of games, video games, as this brand new thing that’s popped up. But of course games have been around forever. Most games are based on some fundamental play experience that at some point becomes formalized. There are different connotations to play, and with that formal rules. You might play with others, or by yourself, the play might be a zero sum game, or not. These are just a few specialized versions of play in my mind.

Scott: Are there any play experts you follow?

Will: Not really. There have been a lot of attempts in the game design community to come up with more formal structures of frameworks to understand this. I think we’re just beginning to scratch the surface. They’re looking at the different perspectives on play coming from cognitive science or sociology or evolutionary psychology. I don’t think any one of these things is going to capture the subject completely. You have to triangulate from all these different perspectives.

Scott: Do you think the vocabulary around play and around games is evolving?

Will: In general, yes. A game is like the nucleus of the experience, but it’s not the whole experience. I spend a lot of time thinking about the meta-game, the experiences we’re having around the game, experiences that are the larger iceberg. For example, The Sims is a game on some level, where you can play with goal structures and rules. However, there’s a larger game where people make things and tell stories about the game. Then they try things with online communities. These are the things that people do outside the game. It is what I call the meta-game. To me, the more successful games are the ones that spark these larger meta-games.

Scott: You mean bringing the play or the game experience outside of the game, in some kind of social context, where people can talk about and interact around the game?

Will: Yes, in some sense the game in the player’s minds goes from being a specific entertainment experience to becoming a tool for self-expression. At first they were playing for the fun, just exploring. Then they start realizing they can be expressive with it. It’s almost like playing a musical instrument. At first, you experiment and press buttons. At some point you realize you can compose music. You might even start to perform. Eventually this toy becomes a tool to express one’s self.

Scott: Is it accurate to say that the opportunity for creative expression is also a central part of your games?

Will: it’s one of the more powerful benefits of technology. We can do things now that allow people to come in and craft more interesting experiences and share them with others. Somebody can take something from their imagination, create an external artifact, and then share it. They can even collaborate on larger imaginary structures. This is something that used to be confined to a small number of people that had very high skills in language. These individuals could write a book and describe some imaginary world, like Alice in Wonderland. But not many people had that skill set. Now average people are getting these tools that empower them, to create entire worlds, external to their imagination, to share with other people.

Scott: You have this amazing ability to translate complicated systems into successful play objects. What is your thought process?

Will: First, how much are these things representations of the real world? When I get started it’s usually with something that contains some aspect of the real world that fascinates me. I’ll start to imagine if I had a toy planet, what kind of things would I want to do with it? What kind of processes would I like to see? By connecting the toy to real world, it maintains a relevance. Later that toy becomes the scaffolding for building a more elaborate model. When people get to the point where they realize the toy’s limitations, they start discussing and debating what their more elaborate model is relative to that toy. When players first started playing SimCity they didn’t know what was going on. They started building things, they started exploring what caused land value to go up or down, they explored issues around crime, or pollution. Eventually they get to a point where they say, “I don’t think that’s the way traffic really works” or “I don’t think the land value model is very accurate because of this or that.” They could not have formalized these thoughts without the toy. When a player realizes the limitations of a toy, the user has created a better model for themselves internally that transcends the toy.

Scott: Once a certain of level of mastery is achieved with a game, that’s the point when a player will go out and look for additional information to improve upon those models, those systems that they have in their mind?

Will: Yes, that’s the real model we’re building, actually. The computer is really just a compiler for that model.

Scott: What you have described in a sense are games that are digital manipulatives. Tangible manipulatives are a big part of the Montessori world and early learning. Sometimes I hear educators debate the benefit of digital manipulatives over tangible ones. Even if a digital manipulative doesn’t perfectly represent a system, they lead a user in a direction that helps facilitate further learning and growth and discovery that is more accurate and representational of the actual model.

Photo above: The typical Montessori learning experience is based on time with tangible manipulatives, such as these base 10 beads. There’s 1 bead, 10 beads, 100 beads, and 1, 000 beads, in the form of a block. These physical manipulatives help young learners understand small and large, base-10 counting, and maybe even geometry (point, line, plane, volume). Substitute beads with the elements of a city, where you can freely experiment with a different kind of units and rules. Get the idea?

Will: Think about it. That’s what we call the scientific method. Quantum mechanics does not describe, is not reality, but it’s our best model so far for describing what we observe to be reality. it’s not the first model we built to describe it and it’s not the last model we’re going to build either. Each model is making a more accurate understanding of reality. They’re all just models and none of them are accurate representations of actual reality.

Scott: Does the knowledge a user gains through game play transfer into the real world? Do you have an example of people playing games where the user transferred something they learned from a game into the real world?

Will: There are a lot of things people learn from games that can’t be measured on any test. On the surface games don’t necessarily feel like education. But when you look deeper into them they really represent a fundamentally deeper level of education. There’s a common story I hear from players of The Sims. Someone will be playing the game and they really get into it. They make sure to take care of the basic needs of their Sims, getting them fed and rested before they go to work the next day. These players can get totally obsessed over making their virtual lives perfect. In doing so, a Sim might get a promotion at work the next day. At some point many players experience an “a-ha” moment — that its 2:00 in the morning, and they have to go to work the next day. Then somehow the players understand that they were taking better care of their Sim than they were of themselves. They were making sure their Sim got to bed on time, was well rested for work the next day, while the players were staying up late playing this silly computer game. For these players this is where they started understanding the strategy within the Sims as a time management game. it’s a game where you juggle many factors. Sometimes a player will step back for the first time and see their real life as a strategy game. As a player, day to day, hour to hour, minute to minute, they were making resource management decisions that would impact their Sim in the short term and long term. Then there’s the paradigm shift: What if your real life was a game, and you actually had these resources, and had to develop structures, how would you play it? This is one of those things you’re not going to measure on any standardized test. Through playing the player would walk away from the game thinking deeply about every aspect in their life. “Do I really need to do this now?” or “Should I really spend that money?” For the first time, the game caused them to clearly see the decisions they were making in every day life.

Scott: If the game is the model of a system, which happens to loosely or exactly parallel your own life, at some point, you might reach that a-ha moment.

Will: Right. People who think of themselves as really good strategy players, for some reason never think of their real life as a strategy game. If I were to treat my life as a strategy game how would I play it?

Scott: Will, thanks very much for sharing your thoughts on play, learning, and games. While we have talked about a variety of inspirations and influences across a number of professions, is there one person that has done more to shape your thinking than any other?

Will: My mother, Beverlye Edwards. She supported me with all my crazy ideas as a child. If there was something I was interested in trying or doing, she believed that I knew what I was doing, even if at the time certain ideas seemed slightly odd. Just her believing in me allowed me to keep on trying new things, made me believe in myself, made me confident that I could do something big, something special. I thank my mother, for everything I have, everything I achieved, for her wonderful spirit and the great support she gave during my childhood years and in the years thereafter. I credit all my success in life to her unconditional belief in me and support in my trying something new.

Linkography:

- NY Times – The Long Zoom, by Steven Johnson

October 8, 2006 - TED Talk – Will Wright makes toys that make worlds

March, 2007 - NY Times – SimCity Living

November 21, 2008 - Maria Montessori: The 138-Year-Old Inspiration Behind Spore

March 29, 2009 - Jeff Braun presentation at Dust or Magic Design Institute

November 1, 2009 - The Man Behind Spore Explores Gaming as Learning

February 5, 2011 - Huffington Post – HiveMind Creator Will Wright Hopes To Turn Real-Life Into A Game

January 2, 2012