The following is a cover story I wrote for the Summer 2014 issue of iKids Magazine.

In this blog version of the article I’ve included some additional information that didn’t make it into the magazine. I originally wrote this piece to discover what elements help a kidtech business succeed, and what part does geography play, if any, in the growth and success of that business.

I also wrote this piece because I’m exploring larger business ideas in the kidtech space. If you’re a like-minded entrepreneur or investor interested in engaging kids through the latest technology or digital device, send me an

email. I look forward to having a future conversation with you.

Note, dollar amounts mentioned in this article represent US or Canadian dollars, depending on the country being discussed.

In this developer’s eye view of the North American children’s tech startup landscape, 360KID founder Scott Traylor finds flourishing life—and dollars—in some pretty exotic places beyond New York and San Francisco. You may never look at Pittsburgh the same way again.

As a Boston-based developer of children’s games, I’m well aware of life outside the confines of San Francisco and New York. Of course, many kidtech startup businesses can be found in these two cities, with Toca Boca, Duck Duck Moose, Fingerprint, Curious Hat, Wanderful, Launchpad Toys and ToyTalk all dotting the Bay Area. And Tinybop, Hopscotch, Ruckus, Speekaboos, Hallabalu and MarcoPolo—to name a few—having set up shop in the Big Apple.

In terms of venture investments, in the last five years in San Francisco and New York City alone, venture organizations closed more than 3, 300 business deals in Silicon Valley to the tune of $31.5 billion. New York saw more than 1, 200 deals close with more than $8 billion invested. However, only the tiniest sliver of these investments went to fund kidtech business. Less than two-tenths of one percent, or $52 million, has been invested in kid-based technology companies in San Francisco in the last five years. An even smaller amount, just under $34 million, was invested in New York City during the same period. The capital is there, no doubt, but it’s not necessarily flowing in the direction of kid-centric businesses.

A closer look at thriving startup communities specifically in Boulder, Colorado, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Kelowna, Canada, have offered refreshing insight into what it takes for a kids tech business to grow and succeed. Business success in the kids space isn’t simply an entrepreneurial stew made up of creativity, talent and perseverance. It’s about access to capital, and it also has a lot to do with where you start your business geographically.

While the following new companies run the gamut from products to service-based in the areas of apps, eBooks, programmable robots and related interactive media, common threads across these three cities in which they are housed include a willing investment community, a local ecosystem that supports new business, entrepreneurial events that encourage business leaders to exchange ideas, and local universities where intellectual curiosity and talent can be shared with entrepreneurs.

BOULDER, COLORADO

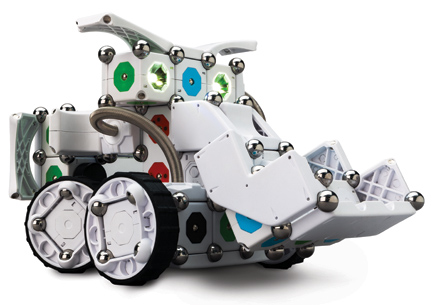

The startup and venture capital scene in Boulder has grown significantly over the last two decades. In the last month, Boulder actually exceeded New York kidtech investing, reaching a total of nearly $41 million in the last five years. Overall, Boulder is a thriving startup Mecca across many technology sectors, and the kidtech offerings based there are heavily focused on software, robotics and electronics kits, with honorable mentions including:

- Modular Robotics, a company that sells magnetic cube-like electronic parts that can easily be snapped together and programmed to build robots controlled by a mobile device or tablet. Modular Robotics is also a Carnegie Mellon business spinoff. (Photo above is of a Modular Robotics product.)

- Orbotix markets a popular programmable electronic ball called Sphero, and the company’s new product rollout called Ollie, Both Sphero and Ollie can also be controlled through a mobile phone or tablet and have a growing developer community that makes apps that interact with, and control, these robots.

- Artificial intelligence drives the Ubooly mobile phone or tablet friend that can talk to you, as well as listen to what you say. Ubooly comes complete with an accompanying cuddly plush cover, as well as a growing list of stories, interactive activities and games.

- ATOMS, by startup Seamless Toy Company, are one of the latest electronic construction kits that work with Lego, as well as many other construction toys. ATOMS can be controlled by a mobile device and vice-versa The founder of Seamless Toy Company holds degrees from Carnegie Mellon and MIT.

While there are a number of venture capital firms that have helped grow Boulder businesses, two investment groups in particular are behind some of these companies. Incubator group Techstars, which has a significant presence in Boulder, as well as many other cities in the US, and venture investment company the Foundry Group were both founded by Brad Feld. He is particularly interested in growing the digital startup scene in Boulder. Feld believes in an entrepreneurial ecosystem, a vision he’s dubbed as the “Boulder Thesis, ” which suggests that an environment needs a mix of old and new entrepreneurs, inclusive of all kinds of business experience and ability. The ecosystem thrives on meetups, hackathons, conferences, professional get-togethers and business pitch events.

KELOWNA, CANADA

Located roughly 240 miles east of Vancouver and 310 miles northeast of Seattle, Canada’s Kelowna is similar in size to Boulder and has the beginnings of the same entrepreneurial ingredients. A number of seasoned local entrepreneurs have turned their interests toward investing in local technology startups, many of which revolve around videogames, animation, social media and virtual worlds. In terms of local kidtech, the success story of Club Penguin, which was acquired by Disney in 2007, plays an important role in Kelowna. As with other large investment locations, an established leader in the area will often result in the appearance of many small startups with a similar interest over time. High-profile former employees include the likes of Club Penguin’s co-founders, who have moved on to start some of these new companies:

- Hyper Hippo is one such Kelowna startup founded by Club Penguin co-founder Lance Priebe. While Hyper Hippo is a game development company, it also recently launched a new immersive virtual world for kids called Mech Mice. (Photo above is of a Hyper Hippo online game.)

- Lane Merrifield is another co-founder of Club Penguin. He recently left Disney to start a new business called Fresh Grade, which develops classroom management and assessment products that teachers and parents can use to access up-to-the-minute information about their students through a mobile device.

- Just Be Friends is a local-social education platform that connects parents, kids, neighbors and schools to help strengthen local communities. Founded by Janice Taylor, who has appeared on Oprah, the startup initially launched in San Francisco but eventually moved to Kelowna.

- A great strength of Club Penguin is its child-safe chat-filtering technology. The former chat technology specialists for the company started a new online chat-filtering business called Two Hat Security, also known in the industry as PottyMouth, to offer other global kid-focused businesses safe online chat technologies.

Accelerate Okanagan is one local organization that is advancing much of the startup activity in the region. Now in its third year, Accelerate is an incubator for fledgling businesses, and its only requirement is that companies pay a $200 per month assistance fee and monthly rent for office space. Once paid, a host of resources become available, including mentorship, legal advice, business advice, access to talent, and cross-collaboration with other Accelerate Okanagan businesses. The incubator also receives government funding. Currently, roughly 50% of the revenue needed to support incubator initiatives comes from government money, but it’s anticipated that this percentage will drop year over year. In the last two years, Accelerate Okanagan has raised more than $8 million from local businesses and entrepreneurs to advance startups, as well as help fund local area meetings and get-togethers. Unlike other incubators, Accelerate Okanagan does not ask for any equity, which is a rare opportunity—and one that is helping about eight kid-focused businesses right now. Accelerate Okanagan is also watching the growing community of startup successes in Boulder, and has similar plans to expand its own model throughout British Columbia, much in the same way that Techstars has throughout the US.

PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA

Believe it. The Pittsburgh community is playing its part in the startup scene—and it’s brilliant. Pittsburgh also happens to be home to renowned children’s television favorite, Mister Rogers, which is a great place to start the city’s story.

Every two years, a local event called FredForward honors the work and memory of Fred Rogers and brings together some of the greatest minds in children’s media, child development, kid-focused policy initiatives and kid media moguls.

In 2007, Gregg Behr, the executive director of The Grable Foundation, presented the idea for the Kids+Creativity Network, bringing together the region’s educators with technologists, gamers, and roboticists to re-imagining Pittsburgh as Kidsburgh. Since then, the notion has gained attention and support from local businesses, community leaders and foundations that include the Benedum, Hillman, McCune, Pittsburgh, and MacArthur foundations. The network has grown to nearly 2, 000 strong—and kidtech and largely edtech-focused startups are starting to bloom.

While on a somewhat smaller venture investment scale than Boulder and Kelowna, though it has three times the population of both cities, Pittsburgh’s startups, nonprofits and schools can collectively receive grants and services from such intermediaries and accelerators as the Sprout Fund, the Allegheny Intermediate Unit, Innovation Works, and the Thrill Mill. The Sprout Fund, for instance, offers grants that range from $1, 000 to $15, 000 six times a year that help carry out the idea that will advance the interests of digital, maker, and STEAM learning.

Just one of many examples of this kind of grant/community collaboration in action, a for-profit startup called Zulama, working with the local educational non-profit Allegheny Intermediate Unit (AIU) developed a program for 9th and 10th graders called the Game Design Boot Camp. Together they defined an unbelievable opportunity for high school students to explore game design. Working with game design experts, students learned how to develop their own original games and received high school credit for completing the program. AIU was the primary grant holder who promoted the opportunity to 42 different school districts. Zulama provided expertise, talent, content and curriculum to students. The grant offered scholarships for 20 students, though more than 75 teens applied.

For its part, Carnegie Mellon University encourages entrepreneurship through CMU faculty and students, making it easier for them to spinoff their own tech businesses. The university implemented a technology transfer program called “Five percent, and go in peace” that allows faculty and student spinoffs to use intellectual property owned by the school for a 5% stake in the startup’s future success. Looking around the Pittsburgh area, it’s an incredibly successful program that spawned a record 36 new companies in 2013 alone. Here are some notable newcomers to Kidsburgh:

- BirdBrain Technologies sells electronics kits where kids combine arts & crafts materials to create their own programmable robots. BirdBrain is also a Carnegie Mellon spinoff. At press time, BirdBrain just launched a Kickstarter campaign for its new electronics kit, the Hummingbird Duo, and has exceeded it’s goal with 16 days left. (Photo above is of a BirdBrain crafting and robotics kit.)

- Digital Dream Labs mixes programming and video game controls. Digital Dream Labs developed physical puzzle pieces that are placed strategically on a holding tray. Each puzzle piece contains instructions that are sent wirelessly to a tablet or mobile device to control a videogame. All three Digital Dream Labs founders are Carnegie Mellon graduates.

- Zulama is an online community for teens that helps teach design, programming and art creation for videogames. Zulama also develops many high-interest online courses in subjects teens are passionate and have great interest in.

- GenevaMars develops story-based, character-driven learning apps that are fun and educational for kids. Its team is made up of artists, producers and educators from Carnegie Mellon, the University of Pittsburgh and the Art Institute of Pittsburgh.

GOING NATIVE

Any city that has a strong entrepreneurial environment will often host startup events throughout the year, offering insights and wisdom on how to fund your business. During one recent startup event in Silicon Valley called The Perfect Pitch: Connecting with Investors, about 120 entrepreneurs attended looking for a leg up on how to grow their businesses to the next level.

“If you are from outside the area I recommend that you ‘go native, '” says Bill Reichert, the Managing Director of Garage Technology Ventures, a venture funding company co-founded by industry giant and evangelist Guy Kawasaki. “One of the great things about Silicon Valley is if you come here we will embrace you, we will love you, and we will smile, but if you are a visitor, we will not fund you. If you’re serious about wanting to plug in to Silicon Valley, that’s what I mean by saying ‘go native.'”

There is an element of truth to going native, at least in terms of securing seed funding or joining an incubator to get a kidtech idea off the ground. Going native is not an absolute, but it does appear to make a difference in getting started. Can an outsider succeed in one of these regions? Maybe, but digging down into who gets funded and who doesn’t, going native appears to be a very attractive component for investors. Investors like the idea of being connected, which can be a hard thing to do from afar.

NOTEWORTHY MENTIONS

There are a few businesses that don’t fall cleanly under the category of kidtech, or do not hail from one of the above mentioned cities, but they are kid-related businesses worth noting.

- Washington, DC-based Zoobean launched in 2012 and is a parent-driven online recommendation service that curates apps and books for children. The company also recently made a big splash on the reality startup show Shark Tank. Zoobean landed $250, OOO from one of the show’s investors, Mark Cuban, bringing its current fundraising tally to $1.2 million.

- Nix Hydra is a teen girl gaming company based in Los Angeles that has attracted a lot of attention with its first app release called Egg Baby which has been downloaded nine million times. The company just landed $5 million from the Foundry Group.

- Another recently funded and very interesting startup is a company called Pley, founded in 2012. What’s Pley’s million dollar idea? (Or their $6.7 million venture backed idea?) Renting Lego kits. Yup. Think Netflix, but with Lego.

- Fitwits is a non-tech kids company in Pittsburgh. Their specialty is selling card-based games that encourage kids through play to make healthy eating choices.

- Another business with an active, high-profile Kickstarter campaign is from LeVar Burton of Reading Rainbow fame. His L.A.-based eBook business, RR Kids, was looking to raise more than $1 million to expand its subscription-based children’s eBook offerings. At press time, RR Kids had exceeded its goal more than three times over.

- And a noteworthy group of companies; First, you’re probably familiar with the much talked about girl-empowerment toy company GoldieBlox. They had a massive hit through Kickstarter, raising almost $289, 000. GoldieBlox also won a national startup competition for a 30 second spot on the Superbowl. Well, there must be something going on just outside of San Francisco area where GoldieBlox is located. Two other local girl-powered, construction-based toy companies also launched around the same time, and also landed seed funding through Kickstarter. Roominate landed almost $86, 000 and Build & Imagine captured $30, 000.

LESSONS LEARNED

So what is it that’s needed for a kidtech business to grow and succeed? Tenacity, focus, business endurance in the face of incredible odds, leadership skills, creativity, a passion for kids. The answer includes all of that, but so much more.

While any kid business can succeed in any location on the planet, Boulder, Kelowna, and Pittsburgh, as well as the bigger funding locations like San Francisco and New York City, all of these areas provide invaluable support structures, which are a main ingredient needed for kidtech businesses to succeed. Venture funding, angel investment, foundation grants, friends and family fundraising, and even local and federal government supports (including tax incentives) are some very important ingredients as well. Access to other entrepreneurs that have an understanding of your industry’s needs, who can share experiences and toss about new ideas. Access to local colleges and universities, where not only talent and innovation can spur from, but also new business spinoffs as well. Ultimately, the invaluable support of an understanding community, both business and non-business alike, may be the most vital ingredient. Toss all of these items together in a large bowl, sprinkle with a wish, a prayer, some blood, sweat and tears, then serve. If the combination does not show early signs of success, start over, mix together again, but this time add a larger scoop of community.

Average Rating: 4.8 out of 5 based on 257 user reviews.